In the intricate dance of medical interventions, oxygen therapy stands as one of the most fundamental and life-sustaining. Yet, a pervasive and potentially dangerous myth persists within both public consciousness and, at times, clinical practice: the belief that a higher concentration of delivered oxygen invariably translates to a more effective and beneficial treatment. This oversimplification, while born from a place of wanting to provide the utmost care, ignores the delicate physiological balance our bodies maintain and can, in fact, lead to significant harm. The administration of oxygen is not a blunt instrument but a precision tool, one that requires a deep understanding of respiratory physiology to wield correctly.

The very premise of "more is better" seems intuitively logical. When a patient is struggling to breathe, the instinct is to flood their system with the vital gas they are lacking. We see the oxygen saturation percentage on a monitor dip below the desired 94-98%, and the immediate reaction is to turn up the flow, to switch from a nasal cannula to a non-rebreather mask, to do whatever it takes to get that number back into the green. This reaction, however, treats the number on the screen as the sole target, neglecting the complex patient behind the data. Oxygen is a drug, and like any powerful medication, it has a therapeutic window, a dose range within which it is effective and outside of which it can cause toxicity or other adverse effects.

The Physiology of Gas Exchange: A Delicate Balance

To understand why high concentration does not equal high efficiency, one must first appreciate the elegant mechanics of pulmonary gas exchange. The primary driver for us to breathe is not, as many assume, a drop in oxygen levels, but a rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) in our blood. Specialized chemoreceptors are exquisitely sensitive to the concentration of this waste gas. In certain conditions, most notably Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD), the body adapts to a chronically high level of CO2. The chemoreceptors become desensitized to CO2, and the primary stimulus for breathing shifts to a relative lack of oxygen, a state known as the "hypoxic drive."

Herein lies one of the greatest dangers of indiscriminate, high-concentration oxygen therapy. Administering excessive oxygen to a patient with COPD who relies on their hypoxic drive can suppress their respiratory effort. Their body, sensing a return to normal oxygen levels, loses its primary trigger to breathe. The result can be hypoventilation, a dangerous accumulation of CO2 (hypercapnia), respiratory acidosis, and ultimately, CO2 narcosis—a state of confusion, drowsiness, and even coma. This is a stark example where a high-concentration intervention directly undermines therapeutic efficiency, pushing the patient into a critical state rather than pulling them out of one.

Oxygen Toxicity: The Fire of Life Can Also Burn

Beyond the disruption of respiratory drive, oxygen itself can be directly toxic when delivered at high concentrations for prolonged periods. The air we normally breathe is about 21% oxygen. While our bodies are equipped to handle the reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced as byproducts of metabolism, this defense system can be overwhelmed when the partial pressure of oxygen in the lungs becomes too high. This is a particular concern in critical care settings where patients may be on mechanical ventilation with a high FiO2 (Fraction of Inspired Oxygen).

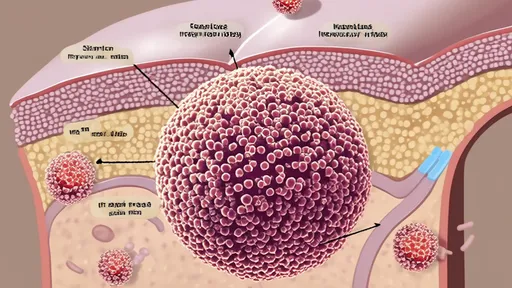

Pulmonary oxygen toxicity can lead to a condition resembling acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It begins with inflammation and damage to the capillary endothelium and alveolar epithelium, progressing to pulmonary edema, thickening of the alveolar membranes, and fibrosis. The very organs responsible for absorbing oxygen are systematically injured by its excessive presence. Furthermore, high concentrations of oxygen can lead to absorption atelectasis. Nitrogen, which makes up the bulk of the air we breathe, acts as a scaffold holding the tiny alveoli open. When it is washed out and replaced with pure oxygen, these alveoli can collapse, reducing the surface area available for gas exchange and paradoxically worsening oxygenation. The efficiency of the lung is thus compromised by the very gas intended to save it.

The Cardiovascular Conundrum and Reperfusion Injury

The impact of high-concentration oxygen extends beyond the lungs into the cardiovascular system. In healthy individuals, hyperoxia can cause systemic vasoconstriction, a narrowing of the blood vessels. This can increase vascular resistance and, in the coronary arteries, potentially reduce blood flow to the heart muscle. For a patient with an already compromised cardiovascular system, such as someone experiencing a heart attack or stroke, this vasoconstriction can be detrimental, limiting oxygen delivery to critical tissues at the precise moment it is needed most.

Another critical scenario where high-concentration oxygen can backfire is during reperfusion after an ischemic event, such as a stroke or myocardial infarction. When blood flow is restored to oxygen-starved tissue, the sudden influx of oxygen can trigger a massive production of damaging reactive oxygen species, causing further cell death and extending the area of injury. This phenomenon, known as reperfusion injury, is a major therapeutic challenge. In these cases, the goal is not to saturate the blood with oxygen but to carefully manage its level to facilitate recovery without exacerbating the damage. The most efficient therapy is one that is measured and controlled, not maximal.

The Paradigm of Targeted Oxygen Therapy

So, if high concentration is not the goal, what is? The modern paradigm has shifted towards targeted or titrated oxygen therapy. The principle is to use the lowest effective oxygen concentration to achieve a satisfactory oxygen saturation—typically 94-98% for most patients, or 88-92% for those at risk of hypercapnic respiratory failure, like many with COPD. This approach acknowledges oxygen as a potent drug with a narrow therapeutic index. It requires continuous monitoring and adjustment, not a "set it and forget it" mentality.

This is where the tools and clinical judgment come into play. A simple nasal cannula may be perfectly efficient for a patient with mild hypoxia, delivering 24-40% oxygen at low flow rates. A Venturi mask, a key tool in targeted therapy, is designed to deliver a precise, fixed concentration of oxygen regardless of the patient's breathing pattern, making it ideal for COPD patients. The focus is on achieving the physiological outcome—adequate tissue oxygenation without side effects—not on maximizing the input. Efficiency is defined by the benefit-risk ratio, not by the flow meter's setting.

Conclusion: Precision Over Power

The enduring misconception that high-concentration oxygen is synonymous with high-efficiency treatment is a dangerous oversimplification of a complex physiological process. From suppressing the respiratory drive in vulnerable patients to causing direct cellular toxicity and undesirable cardiovascular effects, the unintended consequences of over-oxygenation are significant and well-documented. True efficacy in oxygen therapy lies not in the brute force of a high concentration but in the precision of a carefully titrated dose tailored to the individual's specific pathophysiology. It is a practice that demands respect for oxygen's dual nature as both a life-giver and a potential toxin. The most efficient therapy is the one that achieves the desired therapeutic goal with the minimal effective dose, safeguarding the patient from the hidden perils of too much of a good thing. As we move forward in medicine, the lesson is clear: we must treat the patient, not the number, and wield the power of oxygen with wisdom and restraint.

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Daniel Scott/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Amanda Phillips/Oct 14, 2025

By Thomas Roberts/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By Megan Clark/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By John Smith/Oct 14, 2025

By Ryan Martin/Oct 14, 2025

By Benjamin Evans/Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025

By /Oct 14, 2025